- Home

- Catherine Storr

The Chinese Egg

The Chinese Egg Read online

The Chinese Egg

CATHERINE STORR

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty One

Twenty Two

Twenty Three

Twenty Four

Twenty Five

Twenty Six

Twenty Seven

Twenty Eight

Twenty Nine

Thirty

Thirty One

Thirty Two

Thirty Three

Thirty Four

Thirty Five

Thirty Six

Thirty Seven

Thirty Eight

One

On a dusty glass shelf in the window of the bits-and-pieces, second-hand, pseudo-antique shop, lay the egg.

It had been shaped by hand from a single block of wood. The block of hard, close, finely-grained wood had been delicately divided into pieces that interlocked, each fitting close to its neighbours, cheek to cheek, the jutting wedge of this section sliding smoothly into the angle between the two arms of that. As long as the pieces were put together in the right order by sensitive fingers which could feel the balance of the whole, they held together and made up the perfect egg. Polished outside so that it glowed like burnished bronze, the egg, whole and yet divisible, shone among the junk in Mr. McGovern’s shop on the corner of Printing House Lane and the High Street.

Stephen saw it on his way home from school. He often chose to go that way and have a look, fascinated, at Mr. McGovern’s collection. So many things that you’d think no one would ever want, even new and whole and clean, and that surely no one would ever buy now, tattered, chipped and worn. Looking in the blurry window now he saw draggled feather boas, dirty books lacking spines, cracked plates, cups without handles, sad, meaningless pictures in flamboyant frames, clocks which had stopped years ago and which would never mark any real time again. He saw mirrors, cracked lamps, dingy lace, half-backed chairs; and in the side window, where the small objects were displayed, he saw tarnished paste buckles, dusty velvet, the chipped sheen of imitation pearls, a string of child’s coloured beads, gilt brooches, Woolworth jewellery discoloured by age. Among them, different because it was real and had been made with skill and with love, he saw the egg.

He went in and bought it. Mr. McGovern who was elderly and, in spite of his name not at all British, would have liked to haggle, but Stephen wasn’t interested. He was also embarrassed. He wanted the egg and he didn’t want to have to pretend that he wasn’t going to pay for it. When Mr. McGovern said “Two pounds”, perhaps believing that a boy at school wouldn’t have so much, Stephen agreed at once.

“I’ll have to go home to fetch it.”

“I can’t keep anything for you. The peoples come in and say ‘Keep, keep’, then they don’t come back, I lose the money.”

“You still have the thing.”

“Other peoples want and I don’t sell because of the first peoples. So I lose.”

“I’ll be back in five minutes. It’s only round the corner.”

“So everyone tells me, then they don’t come back.”

“You could keep it five minutes.”

“Five then, by my watch.” Extraordinarily his watch was going. All those dead clocks in the shop brooded, stopped for ever at different hours anything from one to twelve, but Mr. McGovern’s nickel-plated modern wristwatch told the right time. Stephen ran home, let himself in, collected the notes from the purse in his desk, and was back before the nickel-plated five minutes were past. By the grandfather clock just inside the shop door his errand had taken no time at all.

“Is a beautiful piece of workship,” the old man said, now apparently unwilling to part with the egg.

“How many pieces?” Stephen asked. He could just slide a finger-nail between two.

“I haven’t counted. Twenty? Twenty-five? Is very difficult puzzle. You separate, maybe you never put her together again.”

“Isn’t there a plan? Instructions?” asked Stephen, child of his age, accustomed to explanations and printed instructions, diagrams and the scientific approach to every sort of mystery.

“No plan. Is a secret egg. Is Chinese. You find her out,” Mr. McGovern said, and disappeared into the dark recesses of his shop. Stephen, holding the egg carefully in one hand, turned and left.

And then outside, it happened. He tripped, as he stepped out, on an uneven paving-stone, stumbled forwards, saved himself, just didn’t go right down. But his hand opened and the egg sprang from it in spite of his desperate, just-too-late grip on its slippery surface. It seemed to rise into the air and fall slowly, in a parabola, a curve like water from a fountain. It hit the ground with a dull thud and burst, like a wooden firework, into pieces. Stephen saw odd-shaped bits of wood lying round his feet, many, meaningless, robbed of all significance by being divided. His egg had disappeared. He was left with a lot of spillikins of different shapes, but of no importance.

He began to collect them. He might even have found all of them immediately if it hadn’t been that at that moment the trail began back from the local comprehensive school. Boys and girls of all ages and sizes were surging through the street on their way home at the end of their school day. Stephen had to dodge through them, avoid their feet, as he searched for the hooked and angled shapes. “Excuse me,” he said desperately, rescuing a small mallet-shaped fragment from under the heel of a Brunhild in a grey duffle coat. “Hi! Don’t step on that!” to a boy in jeans and an Aran-type pullover. He dodged and grabbed and the chattering, uncaring crowd poured past him like a river in flood. When he finally stood up, dishevelled, hot and angry, he’d collected more than twenty pieces; he couldn’t be sure of the exact number. He put them loose in his pocket and went moodily home.

Two

Vicky got home that same Friday evening to find her Mum cutting out all over the kitchen table. Bits of tissue paper pattern floated off the back of a chair as she opened the door. The table was bright with dark blue polished cotton scattered with little flowers of shocking pink.

“What’s it going to be?”

“Dress,” her mother said, her mouth full of pins.

“Super! Who for? You?”

“Wait a minute while I get these pins in.”

She anchored one of the extraordinary-shaped bits of paper on to the blue. It looked like a pale island in a sea of blue and pink. Then she said, “For you. Summer dress.”

“Can I see the pattern?”

She saw it and was pleased. Her Mum generally chose well, and her dress-making, if not professional, almost always had a sort of style. She never finished the seams off inside as you were supposed to, and sometimes, from not reading the instructions carefully enough, she made silly mistakes, Once she’d made the whole dress back to front, puzzling all the time why the darts came in such funny places. Even so it had turned out all right. She had a good eye for colour, often adding extras, a braiding, big buttons, cuffs of a different material, which turned the clothes she made into something special.

“Are you making one for Chris too?”

“Not out of the same material I’m not.”

She never did. Vicky and Chris hadn’t been dressed alike ever since they were tiny. It was only sense. They looked quite different. Chris was slender, with mid-brown to reddish hair, and she was pretty. No, she was more than pretty, she

was fabulous. Boys took one look at Chris and then pursued her. Vicky was not fat, but beside Chris she looked big. She had big bones, too much nose, too big a mouth, long hands and feet. Her hair was dark and absolutely straight. Chris’s was just wavy enough never to look untidy, Vicky’s always did. Chris’s skin was fair, Vicky’s was dark. Chris’s eyes were a wonderful clear blue, Vicky’s were greeneryyallery. People often said in surprise, “Are you really sisters, you aren’t a bit alike?” Then after they’d seen the girls’ father they often said, “Of course. Chris is just like her Mum, isn’t she? And Vicky’s like her Dad.” Sometimes Chris and Vicky agreed and let it go, sometimes they explained. There’d been a time, when Vicky was small, when she’d explained every time, thinking it was fun to surprise them. Now she wasn’t so sure.

Chris came into the room and said, exactly as Vicky had done, “What’s that you’re making?”

“Dress for Vicky.”

“Can I see the pattern?”

“Help yourself. And don’t upset my pinbox.”

“Super!” Chris said, just as Vicky had done.

“Glad you like it.”

“Going to make one for me too?”

“If I’ve time before the summer comes.”

“I don’t think it ever will. You’ll have plenty of time. It’s freezing for April.”

“Only just April today.”

“Spring holidays start next week. It ought to be warmer now.”

“May’s often a nice month,” Mrs. Stanford said hopefully. She pinned a long wedge-shaped piece of tissue paper to a length of the material and said, “That’s the three skirt pieces. I’ll clear off and get tea.”

Tea was high tea. Sometimes Mr. Stanford got back, in time for it, sometimes he didn’t. This was partly because he worked on shifts, partly because Mrs. Stanford kept irregular hours herself. She was good about getting the girls’ breakfasts when they had to get to school on time, but for the rest of the day she pleased herself. It wasn’t unusual for them to come back from school at half-past four and find that she’d only just got herself lunch. High tea could be any time between five and nine in the evening; it depended on friends, on shopping, on Mrs. Stanford’s own appetite, on television programmes, on the day of the week. Vicky and Chris were so used to it that when they visited houses where meals were always at fixed hours, they were faintly surprised. If tea was late and they were hungry, there were always biscuits in a battered red tin, coke in the fridge and often bits left over from the night before in the larder. Chris ate everything and never put on an extra pound; Vicky had to watch her weight. She was the one who sometimes rebelled against the endless meals of baked beans, cold sliced ham and sliced white loaf, spread with lashings of butter. Not that she didn’t like it, but it put pounds on her.

Tea today was tinned red salmon and salad, followed by red jelly. Plus bread and butter of course. Vicky was ravenous, the school lunch had been more uneatable than ever. She and Chris ate a huge tea, then sat round groaning.

“I’m too full. Wish I hadn’t eaten that second lot,” Chris said.

“What’re you going to write about for English?” Vicky asked.

“They’re a rotten lot of subjects. I don’t want to do any of them.”

“I don’t mind the one on Macbeth.”

“You must be crazy! It doesn’t mean a thing.”

“What is it?” Mrs. Stanford asked, licking a thread before putting it into the eye of her needle.

“About how the witches knew Macbeth was going to kill Duncan,” Chris said.

“No it isn’t. It’s whether Macbeth would have done anything about it if he hadn’t been told he was going to be king,” Vicky said.

“What’s the difference? They told him the future, didn’t they?”

“But what’s interesting is whether he’d have murdered Duncan if they hadn’t said anything.”

“But he did murder Duncan. He couldn’t have been king without,” Chris said.

“Only did the witches make him do it by telling him first?”

“Is that what you’re going to write about?” Mrs. Stanford asked, half attending.

“I might. I’ve got maths as well. And history. It’s going to take me hours.”

She turned her school bag out on to the cleared table. There was a cascade of books, exercise books, three biros, an elderly rubber, two set squares and a pencil, a ruler, a packet of Polos and a piece of wood.

“Can I borrow your rubber? I’ve gone wrong already,” Chris said reaching for it. Her fingers met the piece of wood first, and she said, “What on earth’s that? It doesn’t look like anything.”

“I dunno. Saw it in the gutter. Somehow it looked nice. As if it meant something.”

“Funny shape,” Chris said, holding it up, a stalk of wood with a wedge-shaped excrescence each end.

“Piece of something else, if you ask me,” their mother said.

“The ends are sort of polished,” Chris said.

“What can you do with it? If it’s just a piece of something it isn’t any good, is it?”

“S’pose not. I just sort of liked it. It looked somehow. . .”

“What, for Pete’s sake?”

“I don’t know. As if someone had meant it to be that shape. That’s all.”

“You’re crazy,” Chris said affectionately.

“It feels nice. Chuck it over. It might bring me luck,” Vicky said, frowning at her maths. But she didn’t have luck with her maths. Every single problem she tackled came out hopelessly wrong.

“Why Vicky?” Mr. Stanford said to his wife later that evening, when the girls had gone up to bed, and she was sitting at the sewing-machine, feeding the blue and rosy material through its predatory foot.

“They’ve both got to have new summer frocks.”

“Why Vicky first? Why not Chris for a change?”

“To tell you the truth I bought this material for Chris. Just her colour, it is.”

“Why make it for Vicky, then?”

“I know it’s stupid, but every now and then it comes over me that Chris is ours, and she knows it. Chris is safe. As safe as a child can be. And Vicky isn’t. I want to make it up to her.”

“That doesn’t mean you have to be doing things for Vicky that you don’t do for Chris.”

“I don’t in the ordinary way. I don’t think about them like that. It’s different too, Chris being so pretty. You know, I feel God’s been unfair making Chris the pretty one and Vicky plain. Well, not plain exactly, but she’s not like Chris.”

“That she’s not,” Mr. Stanford said.

“She’s a nice girl. You love her too,” his wife said.

“Of course I do. Only I don’t forget she’s not mine. Nor yours.”

“That’s what I mean. However much we look to her as if she was our own, she can’t ever be the same. There’s always the thinking, ‘Perhaps that’s her mother coming out,’ or, ‘Who was her father, when all’s said and done?’ That’s why I feel different about her.”

“That’s why you give her Chris’s summer frock?”

“Maybe. I don’t know. I just feel I owe her something, that’s all.”

“You owe her? I’d say she owed you. There was no call for you to bring her home the way you did.”

“Let’s not have that again. You agreed at the time, you know you did.”

“Right. But I never. . . .”

“And she and Chris make a fine pair, don’t they, now?”

“They’re all right,” Mr. Stanford said without enthusiasm.

“And Chris would have been lonely.”

“I won’t have you upsetting yourself about that.”

“I’m not upsetting myself. And Vicky’s a good girl.”

“She’s all right.”

“Clever, too.”

“She’ll never be a patch on Chris for looks,” said Chris’s father proudly.

“We couldn’t have done without the two of them.”

; “So you say.”

“I couldn’t, anyway. Sometimes. . .” but she didn’t finish the sentence. She’d been going to say that she couldn’t imagine her life without both her own and her adopted daughter, but looking at her husband’s face she decided not to say it aloud. She loved them both. That was enough.

Three

When Stephen had got home and tried to fit the bits of the egg together he realised the truth of what Mr. McGovern had said. It was not an easy puzzle. He’d spent longer over it than he should, considering the amount of weekend homework he had in the sixth form, and by dinner he hadn’t got anywhere near discovering the lie of the pieces. He ate angrily through one of his mother’s experimental dishes, returning the standard “all right” when she asked anxiously whether it was what he liked. He felt furious. He was furious with himself for dropping the egg, furious with himself again for not seeing at once how it should fit together, and furious with his parents for being there, for asking him questions he didn’t want to have to answer, for his mother’s anxiety and her ineptness with food—why couldn’t she just cook roast chicken or beef or warm up frozen food like other people’s mothers? Why did she have to try out fancy sauces and elaborate French ways of messing up perfectly good food which might have been all right if she’d been better at it, but which always, in her hands, went wrong? His father, fortunately for Stephen, was tired, so he didn’t have to answer the endless inquiries into what he’d been doing, what he’d been thinking and why? why? why? all the time. Stephen supposed this went with his profession and it seemed to have become an inescapable part of his private life as well.

“What are you going to do after dinner, darling?” his mother asked as she stacked plates for Mrs. Noble to wash up in the morning, and Stephen said, “Work, I suppose,” wondering what his father would say if he’d answered that he was going to try to mend a broken egg. He could just imagine how his father’s expression would change to the alert, watchful look which meant that he thought for once he was going to see into Stephen’s mind. He’d say, “That sounds like quite a tricky business. How are you going to set about it?” or, “Now why should you want to do that?” or if he was feeling philosophical, “Interesting concept the egg, as the perfect indivisible whole. . .” or something like that, with a string of the names of all the different tribes in the South Seas or somewhere who worshipped the egg as a god or as a fertility symbol or the token of re-birth or anything else sufficiently far-fetched. Stephen by now knew quite a lot of the jargon, though he couldn’t be sure he always got it right. One thing was certain, though, whatever else his father said about it, he wouldn’t just see it as an egg. That would be too ordinary and simple. It would have to mean something else. Stephen thought that both his parents really made life much more complicated than it need be, since his father would see the egg not as an egg but as a symbol, and his mother wouldn’t just boil it or fry it, but would look up how to turn it into something unrecognisable in one of ‘her foreign cookery books. By the time either of them had finished with it, in fact, no one would ever know it had started life as nothing more than an egg. “Its own mother wouldn’t know it,” Stephen said aloud in the privacy of his room, and laughed and felt better.

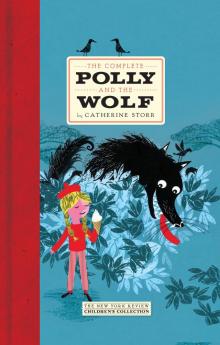

The Complete Polly and the Wolf

The Complete Polly and the Wolf The Chinese Egg

The Chinese Egg The If Game

The If Game