- Home

- Catherine Storr

The Chinese Egg Page 2

The Chinese Egg Read online

Page 2

Probably, just because he felt better, when he looked at the wooden shapes where he’d left them angrily an hour or so earlier, he saw them not as incomprehensible, hostile, separate things, but as having meaning, parts of a whole. He forgot his history essay and the intensive reading he should have been doing around the Metaphysical poets, and sat down at his desk, fingering the smooth pieces of wood. He found that without thinking he’d interlocked three of them together, obviously right. There was the beginning of the outside curve, ovoid, polished. The inner surfaces were plain, that was the only help in seeing how the egg was to be put together. Pleased with his progress, he made the mistake of concentrating too hard, trying to work the puzzle out like an algebraic formula, or a problem in geometry, as if it were a proposition in logic. It was better, he found, if he didn’t think directly about it, but let his fingers play with the pieces, his eyes wander over them; then suddenly it jumped at him, how this angle was made to fit into that, how what had seemed an impossible shape to fit in anywhere turned out to be the king-pin that held, others together. Before, when the pattern had completely eluded him, he’d been working at it too hard; now he played, allowing his mind to wander, thinking of his friends, school, places he’d been to, girls he’d looked at and longed for, music he’d heard. And while he dreamed and remembered the egg grew in his fingers. Like any jigsaw—only this was a three-dimensional one—it got simpler as the pieces to be fitted in became fewer. Even so it wasn’t easy. He stuck at it, with a growing feeling of triumph, for over two hours. It was eleven when he’d got all but the last three pieces into place. It wasn’t until that moment that he realised that although only three pieces remained on the red leather inside the flap of his desk, this wasn’t the total number needed to complete the egg. He fitted them in, with a sort of desperate hope that he’d got it wrong, but there was no doubt. The smooth surface of the egg still showed one or two rectangular gaps where another polished segment should slot in. And though the egg held together, it was doubtfully, hesitantly, without the firm confidence Stephen had sensed in it when he’d first held it in his hand. There was at least one bit still missing; he must have overlooked it in the street. He’d go and look for it first thing next morning. It was a Saturday, fortunately. He was determined to find it. He went to bed angry again, stayed awake longer than usual, raging against the luck that had made him trip just at that psychological moment, and overslept the next morning. He didn’t get out to begin his search until after ten.

Chris and Vicky went out shopping every Saturday morning. This Saturday was no different from any other to start with. They did the boring stuff—that meant the household shopping—first, then went to look for the more interesting things. Chris wanted shoes. Vicky wanted a slide to keep her straggling hair off her face; astonishingly she found immediately exactly what she wanted, made of pale fine cane woven into a sort of flat knot. “Marvellous, you’re so dark. Keep it on, Vicky, it’s great,” Chris said. Looking in the mirror Vicky saw that it was true. The slide, the way Chris had looped her hair off her face, made a new, different Vicky. Not pretty, not ravishingly pretty like Chris, but a girl with a style of her own. She almost smiled at her reflection, then her eyes took in the sloppy pullover she’d been wearing for the last year, faded jeans stretched a little too tight, and beside her, Chris, in almost equally old clothes, but somehow looking finished and put together just right, and sure of herself in the way that perhaps only a girl who has been pretty, without effort, from babyhood, can be. Vicky scowled at her own reflection, then cheered up and bought the slide. It was miraculously cheap. She came put of the boutique saying, “Lucky! We’ve both been lucky, your shoes and now this.”

Chris said, “Your silly bit of wood you found. Think it really works?” Vicky put her hand in her pocket. She’d forgotten it, but it was there. She started to say, “That wasn’t the sort of luck I meant,” when the thing happened.

They were on the pavement outside the delicatessen, just by the pedestrian crossing, the one that Mum always said was dangerous; the road was too wide, a driver coming up on the outside couldn’t see who’d stepped off the pavement. Vicky wasn’t really looking at it, but it flashed suddenly in front of her eyes. The funny thing was that what she saw was in a sort of frame, like a small bright picture surrounded by odd, dark, angled shapes like the top of a tower, like battlements. In the bright picture, she saw the crossing and an old lady starting to walk across in front of a blue van that had stopped for her. In that instant she heard two sounds. A voice, a boy’s voice, cried out, “Look out!” and brakes screamed. She thought she saw a car coming up much too fast on the further side of the van, she wasn’t sure if the old lady fell. She clutched Chris’s arm and shut her eyes, she didn’t want to see the accident.

“What’s the matter?” Chris said.

Vicky opened her eyes. She saw the boy who had called out, his mouth still open, staring, shocked.

“What’s the matter? You’re hurting,” Chris said.

“The old lady,” Vicky said.

“What old lady?”

“On the crossing.”

“There isn’t anyone on the crossing. What’s the matter? You’re seeing things,” Chris said.

“But I saw her. And a blue van. She was going to be hit.”

“You’re crazy. There isn’t anything like that. Look!” Chris said.

Vicky looked. Chris was right. Traffic was flowing smoothly up the High Street, buses, vans and cars. Three small children with their mother stood on the curb waiting correctly until some kind-hearted driver should stop. No old lady, no blue van. No accident.

“I saw her,” Vicky said again.

“You’ve gone all white. You’re shaking. We’d better go back,” Chris said.

“Wait a minute,” Vicky said. The boy was still there. He was standing quite still, looking at the pedestrian crossing, as if he couldn’t believe his eyes.

He had called out. He must have seen it too.

Vicky felt peculiar. She was cold, but she was sweating. Sound roared in her ears, she couldn’t see properly. She took three steps away from Chris towards the boy, meaning to ask him something, she didn’t know what, but when she’d reached him all she said was, “Chris!” desperately before blackness fell on her like a shower of soft dark feathers.

“Help me,” Chris said to the boy, who stood there staring at nothing as far as she could see and looking, she thought, a bit daft. “Into the caff,” Chris said, pointing to it with her head, and they half carried, half dragged Vicky to a table just inside the door. “Get her head down on her knees. She’ll come round in a second,” Chris said, competently holding Vicky on the chair with one hand and with the other forcing her head down. “It’s only a faint. She used to do it in school prayers all the time, but she hasn’t for ages now.”

If she hadn’t been the prettiest girl Stephen had ever seen, he wouldn’t have stayed. He wanted to get away and try to sort out what had happened. Since that wasn’t possible, he ordered three coffees and waited while the other girl, the not pretty one, sighed and sat up. She looked awful, dead white, with black shadows round her eyes and the hair on her forehead damp with sweat. He preferred to look at her friend.

“Drink your coffee, Vicky. You’ll feel better then,” the pretty one said, and the other girl obeyed without speaking, as if she hadn’t the will to do anything else. “Gosh, I needed that! Thanks,” the pretty one said to Stephen. When she smiled she was prettier than ever.

“What happened?” Vicky asked Chris.

“You fainted. Well, nearly. He helped me get you in here.”

“There was something else. I saw something.” She shivered suddenly and said to Stephen, “Why did you call out?”

He’d hoped no one had heard above the noise of the traffic. He said, “What do you mean?”

She didn’t answer. She had taken a handkerchief out of her pocket and was wiping her forehead on it. She put her hand into her pocket again and took out som

ething else. She held it out to the pretty girl and said, “There was a shape like that round what I saw.” She held the thing up and looked past it at Stephen. He saw, incredulously, an angled piece of wood with a polished surface at either end. He said, “Where did you find it?”

“In the road.”

He said, “It’s mine!”

“What d’you mean, it’s yours?”

In order to keep the egg in its perilous, incomplete shape, Stephen had wrapped it in a plastic bag. He took it out of his pocket now, extracted it from the bag and laid it on the table.

“You see? It’s a piece out of this.”

“How’d it get into the road, then?”

“I dropped it. I couldn’t find all the pieces when I looked for them.”

“I only found it yesterday,” Vicky said.

“That’s when I lost it.”

“It is his. You ought to give it back to him,” Chris said.

Vicky didn’t either offer Stephen the piece or put it back in her pocket. Looking at him hard, she said, “You did call out just now. You said, ‘Look out!’ Why?”

“I heard too,” Chris said, not liking it.

“I suppose I thought. . . I thought there was someone on the crossing.”

“That’s what Vicky said. Some old lady, she said. I couldn’t see anyone.”

“The blue van was right by us,” Vicky said.

“No, it wasn’t. It was a bus, when you said that.”

“It was a blue van. Like that one,” Vicky said, pointing through the window at a van standing stationary farther down the street. As she spoke, it pulled out and came towards them. It slowed as it approached the crossing. This time the picture wasn’t nearly so bright, the sky was grey and there was beginning to be a thin drizzle, but again Stephen had cried, “Look out!” and the brakes screamed again, and Vicky’s eyes shut in a convulsive effort not to know. But this time when she opened them all the traffic had come to a standstill, people were running, there was already a crowd round something lying in the middle of the road.

“Come on. Let’s get out of here,” Chris said, as white and shaking as the other two.

Stephen said, “I’d better see you back.” They left their coffees half drunk and made for the open door. The ambulance had come ringing its urgent warning before they had left the busy street.

Four

“I don’t like it,” Chris said, back at home. They were sitting in the kitchen after a dinner they’d neither of them been able to touch.

“You don’t think I do?”

“Did you really see the blue van that first time?”

“Yes, I did. And it was a car just like the one that—that did it, the first time too.”

“A Jag.”

“I don’t know. You know I’m no good at cars.”

“And you saw an old lady. It was an old lady that got knocked down. I heard them say so.”

“Do you know how bad she was?” Vicky asked.

“They must’ve taken her away in the ambulance.”

“Perhaps she was just stunned.”

“I don’t know.”

They sat and looked at each other.

“D’you think that boy saw it too?”

“I don’t know.”

“He didn’t want to say why he’d said ‘Look out’, did he?”

“I don’t know,” Vicky said again.

“You never did give him that bit of the thing he said he’d lost and you found in the road.”

Vicky took it out of her pocket and put it on the table.

“What did you mean when you said there was a shape like it round what you saw?” Chris said.

“Sort of jagged bits, like this, only dark. In the middle I saw the accident.”

“Suppose you really could see what’s going to happen next?”

“I don’t want to. It was a lousy thing to happen.”

“But suppose you could see something nice? Like who won the Derby. We’d all get rich. That wouldn’t be bad.”

“It won’t happen again.”

“You mean you hope it wont.”

“It won’t.”

Mrs. Stanford came in and sat down.

“Might just as well not have cooked any dinner for all the appetite you two had. Three-quarters of it gone into the dustbin.”

“You didn’t, Mum! Waste,” Chris said.

“Toad-in-the-hole’s never the same warmed up. And don’t you say Waste to me. You should have eaten it, if you didn’t want it thrown away.”

“Couldn’t. Not if you’d paid me.”

“Upsetting, seeing an accident,” Mrs. Stanford agreed.

“Vicky saw it twice.”

“What do you mean, saw it twice?”

“Saw it before it happened.”

“You didn’t, did you?” her Mum asked Vicky.

“I don’t know.”

“But Vicky, you said. . . .”

“I could have made a mistake, couldn’t I?”

Chris always knew when Vicky didn’t want to go on talking about something. She got up now from the table and said, “All right if I wash my hair now, Mum? Will you come up and rinse me when I’m ready?”

“You washed your hair two days ago. What’re you doing it again for now?”

“Wasn’t two days. Was Wednesday. That’s three.”

“Once a week used to be good enough for me when I was a girl.”

“‘Friday night’s Amami night. Take me out and make me tight,’” Chris sang. Adding, in her ordinary voice, “Laurie’s coming to take me out tonight, that’s why I’ve got to wash my hair.” She ducked her mother’s pretended swipe and left the kitchen laughing.

“Well, I don’t know.” Mrs. Stanford said. She looked again at Vicky, sitting across the table and said, “What’s up, love?”

“Nothing.”

There was a pause, then Mrs. Stanford said, “It was the accident, was it?”

“Made me feel shaky, a bit.”

“Is that all?”

“Mm.”

A pause.

“Vicky? There’s something wrong, isn’t there?”

“I just don’t feel too good, that’s all,” Vicky said, looking at the table instead of at her mother.

“Is it the old thing?”

“What old thing?”

“You know. Worrying about your father?”

“Not specially. Not more than usual.”

“I’ve often thought he very likely didn’t know.”

“Didn’t know what?”

“About you. Your mother might not have told him.”

“Why wouldn’t she?”

“Girls don’t always. Not if they’re not seeing the fellow any more, I mean.”

“She didn’t tell you?”

“Not really. There wasn’t all that time. She went so suddenly. That morning she’d been all right, as far as anyone could see. That evening she’d gone. Haemorrhage, it was. They put six pints of blood into her, but they couldn’t save her.”

“Did she think about what was going to happen to me?”

“She did once say she wished someone like me could look after the baby. Not thinking it would be me, I don’t think.”

“Was it because you and she were in bed next to each other?”

“I s’pose that’s how we started talking. And she liked the way I made a fuss of Chris. Cuddled and talked to her. Silly, I suppose. Some of the mothers in there, they hardly used to look at their babies. Couldn’t wait to get out of hospital, put them on the bottle and hand them over to someone else. Perhaps it was because Chrissie was my first, I acted like I did.”

“Did my mother cuddle me?” Vicky asked. She’d often nearly asked this question before, but never quite. Now it came out easily. That was the sort of person her Mum was, warm and easy.

“As if she could eat you. You were what I’d call good-looking for a baby. Neat little face, you had, and thick black hair. Quite long, it was. I remember yo

ur mother showing me how it was almost long enough to plait. About half an inch.”

“Was Chris pretty then too?”

“I’ve never seen such a little horror. Bald, and her face sort of squashed up sideways.”

“Did you mind?”

“After all that trouble? I wouldn’t have changed her for the world.”

“What did my mother say? About my father? Or anything?”

“Told me she hadn’t seen him for months. That was when I asked if her husband was coming at visiting time. Silly question, I should have known better.”

“He was her husband, then? I mean, was she married?”

“I told you, might have been. She called herself Mrs., but then they mostly do. The nurses like it better.”

“She didn’t say anything else about him? My father, I mean?”

“Said once you didn’t look like him. Like her, you were. Dark hair like yours, she had. Lovely girl. I cried so much when she went, I almost couldn’t feed Chrissie.”

“When did you decide you’d take me too?”

“I wanted to as soon as I heard she’d gone. But of course I had to ask Dad. It was his business just as much as mine.”

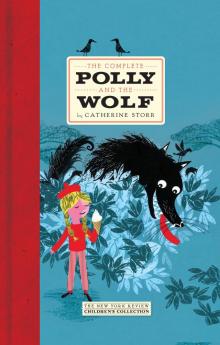

The Complete Polly and the Wolf

The Complete Polly and the Wolf The Chinese Egg

The Chinese Egg The If Game

The If Game